The path to permanent joint bond sales by euro zone governments will be long and bumpy, but Russia’s invasion of Ukraine may have helped clear the way.

The conflict has prompted European countries to pledge more investment in defence and developing renewable energy, expenditure many argue will be best met if the burden is shared.

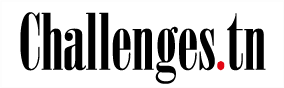

The European Union is already issuing joint bonds for an 800 billion euro ($879 bln) post-COVID recovery fund, but has not mentioned plans for more debt, let alone making the existing facility permanent.

Yet the notion of a permanent scheme has resurfaced in markets and its potential significance is not lost on investors; without considering it an immediate prospect, many are buying bonds from countries that would benefit the most, such as Italy.

Christian Odendahl, chief economist at the Centre for European Reform, sees the war, which Moscow calls a “special military operation”, as a turning point of sorts for Europe, even if the road remains unclear.

It would affect European “integration as much or more as the COVID crisis helped propel a joint fiscal capacity and borrowing, which were both unthinkable when corona was still a beer,” Odendahl said.

Proponents argue that joint bonds would be a powerful signal of European cohesion. They would lift the euro’s profile and expand the European pool of top-rated securities, allowing them to compete with U.S. Treasuries as global reserve assets.

With Germany alone pledging a 100 billion euro military upgrade, spending needs will be colossal. If all European NATO members commit to spending 2% of GDP on defence, overall expenditure will rise by a quarter, the biggest boost in three decades, JPMorgan estimates.

According to BofA, that could require another 150-200 billion euros of combined euro area spending in 2022-23 alone.

Slashing Russian gas ties, as the European Commission plans, could add over 130 billion euros this year to the bloc’s already red-hot energy bill, Reuters Breakingviews calculations show.

While more indebted EU states will be reluctant to shoulder those costs alone, the joint bond debate also speaks to shifts triggered by the COVID meltdown. It brought recognition — even among more frugal nations — of fiscal policy’s key role during times of crisis.

The argument now goes that like COVID, the war is an exogenous shock affecting all EU states, making a joint response more effective than a series of uncoordinated national efforts.

The latest crisis matches COVID as a catalyst for deeper integration, Commerzbank’s head of rates Christoph Rieger said, adding that “a permanent joint EU debt capacity is becoming more likely longer-term”.

NORTH AND SOUTH

France is leading calls for new EU debt, while Germany and other richer bloc members oppose any move toward a fiscal union, with shared borrowing and spending.

They argue that the Next Generation EU (NGEU) — the recovery fund, bonds sales for which started last year — mostly remains unused, with just 74 billion euros disbursed so far.

As it stands, recovery fund borrowing ends in 2026 and the last bonds mature in 2058.

But while the fund sets a precedent, it is not an ordinary tool, says Francesco Papadia, a former market operations director-general at the ECB and now a senior fellow at the Bruegel Institute.

“(Joint bonds) will be possible only in exceptional circumstances, like the present ones … when it will be seen as indispensable to effectively deal with the crisis,” Papadia said, adding he does not believe this is yet clear of the war.

ING analysts suggest lighter kinds of joint borrowing could be more acceptable to the “frugal” nations, for instance modelled on the EU’s SURE unemployment scheme.

PRICING

Bond markets’ recent behaviour demonstrates how the joint fund has boosted the bloc’s resilience.

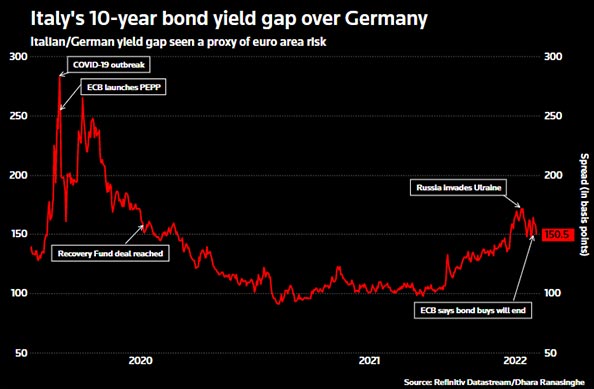

Bond spreads, the premia investors demand to hold debt from a weaker country like Italy or Spain, usually widen in times of trouble. But since the Feb. 24 invasion, 10-year Italian spreads have narrowed 26 basis points.

In other words, Italian premia have eased despite the war, and at a time when the European Central Bank plans to cut back the stimulus which is a key support plank for southern Europe.

The lesson from 2020 is that the ECB can halt spread widening — but a real turnaround was down to the EU’s response, Citi analysts noted.

The NGEU’s creation pulled the Italian/German spread around 33 bps tighter than it otherwise would have been, BofA reckons.

Italian and Greek spreads snapped in 10 bps after recent media reports flagged the possibility of a new joint EU bond scheme.

“The more the market understands that there is political capital for this to happen every time the EU is thrown a challenge, the more it will believe the EU … will eventually get to fiscal union.” Peter Chatwell, head of multi-asset strategy at Mizuho, said.